It is April 27th, and James Nielsen assumes his starting position on the track at the College of Marin in Northern California. His wife, Mimi, is filming him with a Flip video camera. She raises her iPhone to the camera, and focuses on the phone’s timer. “On your mark, get set…” On “Go!” she starts the timer, and Nielsen springs into action. He cracks open a room-temperature Budweiser—because warm beer retains less carbonation than cold—tilts his head back 45 degrees—an angle he knows through studying fluid dynamics will best usher the brew down his gullet—and seals his lips onto the can. It takes him five seconds to drain the can, three seconds faster than if its contents had been simply poured onto the ground. Then—this is very important—Nielsen starts running and tosses the can in the trash.

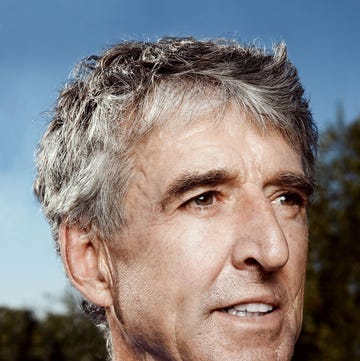

The two-time NCAA National Champion in the 5K runs his first lap very fast. He’s dedicated the past year to training and can now run a mile on an empty stomach in 4:10. With a belly full of beer, he figures he can run 4:20, maybe 4:25.

In the first 400 meters, he feels the triple whammy of carbonation, sloshing liquid, and a furious pace. As he reaches the wooden tray holding the remaining three cans, Mimi yells his split: 70 seconds! He grabs beer number two, jogs forward in the 10-meter drink/run transition zone, and sucks down the liquid in one big inhale. He turns the can upside down over his head to prove it’s empty, then tosses it. He completes lap two in 76 seconds. By now, his abdomen is screaming with a double-sided cramp. He downs another beer—crack, tip, chug—before lap three, which he clocks in 79 seconds, and another before his fourth. On this last lap, Nielsen is schlepping a quart and a half of liquid and a cloud of carbonation in his stomach, an “absolutely terrible” sensation that would derail most humans, but Nielsen has also dedicated the past year to stomach-expansion practice. For tips, he tapped pros like Joey Chestnut, who’s ranked first in the world in competitive eating, having eaten 69 hot dogs in 10 minutes. Nielsen has done things like drink a gallon of milk before running hard around the block and speed-eat a watermelon in one sitting.

The YouTube video of James Nielsen’s run has gotten more than a million views.

After 72 seconds, Nielsen crosses the finish line and Mimi calls out his time: 4:57! In disbelief, she holds the timer before the camera. Her husband has just become the first runner in the world to break the five-minute beer mile. (The previous record was 5:02, set by an Australian named Josh Harris in 2012.)

The breathless runner crumples, hands on his thighs, breathing heavily. Does he want to say anything? Shaking his head, Nielsen says, “That is really painful.”

The next day, Nielsen posts the video on YouTube, and within days it gets more than a million views and a steady stream of online comments: “This guy can chug beers like an animal.” And: “Great job, Beast!!” Nielsen ran and drank with such ease. If the effort assaulted his stomach, it wasn’t apparent while he was running.

And that was the problem—if Nielsen wasn’t obviously suffering during the run, he must be cheating. Turns out, the kind of person who not only watches beer-mile videos but also comments on them is also more likely to think he or she knows exactly how it’s done. Remember that first tossed can? Not good, according to those people. “So right off the bat he ruined the legitimacy by not presenting the can upside down over his head,” wrote one anonymous commenter on the Canadian running site Trackie.ca. “The big idiot didn’t turn the first one over,” wrote another. “He doesn’t even show a close up of the cans to ensure that they’re actually beer,” one decried. “This…is COMPLETE CRAP!!” railed another on Facebook.

Nielsen laughed at the blowback. Replacing beer with water? Right, like he’d infiltrated Budweiser and tampered with the exact cans he’d end up buying, he joked in one interview. No fellow runners? He was in front of a video camera, for Pete’s sake. “I wanted to treat this like a time trial and make sure I didn’t have distractions,” he says. “Vomiting in a beer mile is similar to yawning—once you see someone crack the seal, it can be contagious, and I couldn’t afford to have anyone impact my race against the clock.” And that most egregious of transgressions, the first tossed can? According to the rules posted on beermile.com, overturning an empty over one’s head to prove its emptiness is “strongly recommended,” but not required. Nielsen had stated his intention in the video to flip the can, but simply forgot the flourish after that first Bud.

Regardless, his indiscretions continue to inflame the faithful who still dispute his record. Disciples of the Beer Mile treat its rules like sacred scrolls. Sure, rules are important, but even the guys who created the beer mile are a little taken aback by such seriousness. At its core, drinking beer and running in circles was meant to be about bragging rights, projectile vomiting, top-10 lists—you know, having fun.

Like it or not, beer-mile mania is real. Granted, the actual number of yearly events and participants is hard to pin down—Patrick Butler, creator of the official database, beermile.com, estimates that fewer than 10 percent of race results are posted on the site. Still, the number of times logged into the database has nearly quadrupled, from 421 in 2003 to 1,536 in 2013. Google Trends shows interest spiking in the last couple of years, coinciding with notable beer-mile achievements (like when Olympian Nick Symmonds put his attempt at the world record up on YouTube in 2012—more on that later). Major media are plenty interested, too: When Nielsen broke the five-minute barrier, the Wall Street Journal, USA Today, and Sports Illustrated all picked up the story. But perhaps nothing quite announces legitimacy like a world championship, and this winter, the beer mile gets its first.

Beer-milers themselves are no longer on the fringes, either. They’re in running clubs and startups, on campuses and Olympic teams. Chances are good you know one. In fact, the guys who invented it are now teachers, accountants, IT executives—in other words, well-adjusted folks who could be your neighbors. But back in 1989, they were just seven Canadian runners in their late teens and early 20s, looking for a laugh on a muggy August night.

They came up with their plan during a postrun drink: Swill four beers and sprint four laps—beer, lap, beer, lap, and so on. Adding beer to the mile seemed a fine combination of the group’s primary pastimes that summer. They had become friends through high school cross-country and track; the youngest, Graham Hood—an eventual Olympian in the 1500 meters—was 17, still in high school, and still under Ontario’s legal drinking age of 19. The oldest, at 26, was Kelly Harris, who had coached a few of the guys on their city running team.

Soon after conceiving their plan, they shouldered Canadian-made brews (probably Molson or Labatt Blue; it’s been 25 years) to Burlington Central High School in Burlington, Ontario. Without a gate to climb or much visibility from the street, the track seemed a decent place to start a good night. Each runner lined up four unopened cans of beers for himself at the starting line, and as the sun was setting, the timer started.

Crack, tip, chug, burp, run. The first lap was over fast. At first, the discomfort paled against the excitement of putting their plan in motion, but two or three laps in, the beer and the stomachs stopped getting along. They thought it was the alcohol that would get them—ha! Burping alleviated some of the discomfort caused by swallowed carbonation, but those without that particular skill felt like a shaken-up Coke can. “The fourth lap was a blur—survival mainly,” says Harris. On the last lap, in a crisis of sweat and foam, he sprayed the contents of his stomach onto the infield without missing a stride, and finished third. (This evacuation strategy displeased the others. They claimed it provided an unfair advantage by removing the race’s most challenging obstacle—a saturated stomach. And so the first rule was born that night: If your beer reappears, you run an extra lap.) The strategy that night of winner Tom Jones, then just weeks from his 19th birthday (so not yet legal then, either), was simple: Outrun the alcohol. He clocked a 7:30. “I was fine,” Jones says, “then a couple minutes later, I couldn’t walk.” His buddies had to carry him home. They’d all had a fine time.

As members of that original crew went off to college that fall of 1989, they kept the beer mile alive. At Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, Ian Fallas and Rob Auld recruited more of the party faithful, and by 1992, the beer mile—dubbed the Kingston Classic—was in its fourth consecutive year (and held at dusk at the university’s Richardson Stadium to avoid campus security).

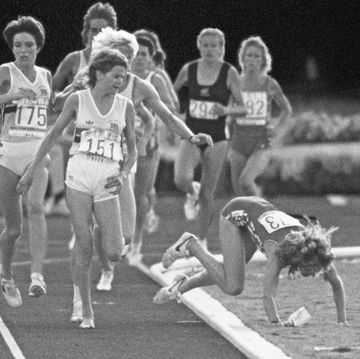

Graham Hood, one of that original crew, arrived at Richardson Stadium for the August 1992 race just weeks after his ninth-place finish in the 1500 meters at the Barcelona Olympics. He may have been good enough to represent his country on a global stage, but as a beer-miler, he was a miserable failure. “My stomach wasn’t built for it,” he says. The Olympian earned himself a penalty lap. (When the group created “Top 10 Reasons to Run the Beer Mile” T-shirts a few years later, number six was: “It’s the only mile where just about anybody could beat Graham Hood.”)

Cookie tossing got the better of many a beer-miler. Of that same 1992 race, Mark Arsenault (nickname: Arse) says, “I wasn’t going to run it. I thought, This is ridiculous. And I’d had a huge pasta dinner. They basically twisted my arm, and then I went and threw up.” Which netted him the number three spot on the T-shirt—“Witness Mark Arsenault’s fabled spin-a-rama.” “When I throw up, I start to spin,” he says. “I probably threw up 75 percent of the time.”

It may all sound rather sloppy and misguided, but the milers weren’t totally reckless. “It was never a leave-a-big-mess, rowdy thing,” says Arsenault. “It was always, do the race, clean it up, leave.” They scheduled races so they wouldn’t interfere with the real work of being a collegiate runner. “During the season, we didn’t drink. So it was usually during the off-season that you let loose a little bit; the rest of the year most of us were pretty serious,” says Arsenault, who no longer drinks beer at all, thanks to acid reflux.

The winner that year was again Tom Jones, who ran a faster mile than he’d ever run sober and set a beer-mile record. Later that night, Jones grabbed a half-full pitcher from a bar as a trophy, hid it under his shirt, and asked his fellow beer-milers to carry him out as if he were drunk (which he was). In front of the bouncer, his friends lost their grip, and Jones, the pitcher, and the beer spilled all over the floor. Jones managed to escape with his clear plastic prize, upon which someone later scrawled in black marker his record time: 6:52.

Inevitably, beer-milers got serious. Guys began training for the event by eating piles of pasta and then chugging beer to expand their stomachs. Milers started wearing spikes, sticking straws into bottles for better airflow, discussing the merits of shotgunning (punching a hole in the bottom of the can to accelerate the beer’s natural exit). It was time for a few rules.

At first, standards were simply verbalized, and added when deemed necessary: No straws, shotgunning, or drinking aids. No wide-mouthed cans (this was before such cans became commonplace). No light beers—brews must have at least 5 percent alcohol. Beers should be opened and consumed within a 10-meter transition zone. Beer, and only beer.

With more rules came more records. In 1993, Ian Fallas ran a 6:30, barely beating Dan Michaluk, a middle-distance runner at Queen’s University. “I was wearing skateboarding shoes,” says Michaluk. “I thought, This is a stupid event; I’ll just go and watch and have some beers. Then I got sucked in and ran it in those shoes and had a stress fracture for the entire fall season.”

Still, the standards were known and followed only within the radius of a few Canadian universities. Through word of mouth and track-and-field email groups (this was the pre-Google era), guys like Al Pribaz, a beer-miler from Queen’s University and the event’s unofficial recordkeeper, started hearing about more and more brew-infused events popping up around Canada and the U.S. Pribaz wanted to compare results, but most races just winged it on the rules—alcohol content varied widely, and some milers drank from plastic cups, which allowed for carbonation to escape. So sometime around 1993 (memories are hazy), in their dumpy living room and over beers (naturally), Pribaz and his buddies put their verbal standards in writing as the Official Kingston Rules. The bullet points outlined: where beer should be consumed; alcohol content; amount; receptacle; a three-beer rule for women (instituted a year earlier in desperation for diversity); a penalty lap for puking; and restrictions against tampering or drinking aids. Pribaz posted the rules on email lists and online track boards, and encouraged everyone to beer-mile in sync. Results began trickling in, and Pribaz eventually created the “Kingston Beer Mile Homepage” and posted them online.

A few years later, Patrick Butler, a computer science major and runner at Wesleyan University in Connecticut, spotted Pribaz’s website. His teammates were planning their end-of-season bash, and Butler successfully lobbied for what was going on up north—a beer mile guided by the Kingston Rules. An above-average collegiate runner, Butler found his calling and won his school’s first-ever beer mile with a 9:12. He was hooked.

By his senior year in 1998, Butler was tracking results from more than 100 beer miles in the Northeast and posting them on a small track-and-field website he maintained, and generally evangelizing the standardization of the Kingston Rules (except for the three-beers-for-women one, which he didn’t include: “That wasn’t going to fly here”). That December, he scooped up the domain beermile.com. He spent a weekend coding the database, and opened it up for results from across the U.S.

Beermile.com became home base for anyone curious about injecting booze into the mile. Newcomers could bone up on the rules, and veterans could enter their results and monitor the leaderboard. Runners from the U.S., Canada, and eventually all over the world logged their race results.

Traffic to the site was slow but steady through the early aughts—sometimes 50 entries a day, oftentimes fewer. It picked up steam with the rise of social media and video sharing in 2004, and by spring of that year, the site boasted 8,000 results.

As search engines like Google and Internet Explorer got more sophisticated, beer-milers emerged from the shadows. “In the early 2000s,” says Butler. “I started getting a lot of requests from people who said, ‘Hey, can you take my name down? Look, I’m really proud of this result, but it shows up first in search engines, and I need to get a job.’ That was very common.” Dan Michaluk, of stress-fracture-from-skateboard-shoes fame, and now an information privacy lawyer in Toronto, worked for years to get his first Google result to show something other than his beer-mile successes (12 results in the all-time top-100 beer-mile results). “I finally got it down to page two, but it kind of lingers there,” he says. The Web did more to promote the beer mile than bragging over a bar table ever could.

If the Internet made the beer mile accessible to the masses, the elites made it aspirational. On December 20, 2005, Canadian Marathon champion Jim Finlayson ran a beer mile as part of a local fundraising event. He chose Guinness for the taste, knowing that its 4 percent alcohol by volume wouldn’t meet official standards. His time, though unofficial, was an astonishing 5:13—nearly 30 seconds faster than the previous record. “I thought it would feel a lot worse than it did,” says Finlayson. “I had no issues.”

Though proud of his accomplishment, Finlayson is a bit wary of the attention the sport is now getting. “I’m obviously not anti-drinking, but I also don’t want drinking to sound cool,” he says. “I appreciate that running is getting attention because of this, and I’m not contra the attention. I’m just not sure how pro I am either.”

Nevertheless, Finlayson’s performance marked a turning point for the beer mile—real athletes taking such a crazy idea seriously gave it new appeal. Beermile.com started getting more than 100 hits a day.

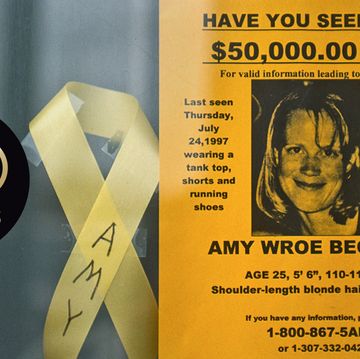

The traffic surge really isn’t all that surprising. Records tend to make the rounds, and with something this ridiculously hard and seemingly ill-advised, word tends to spread even faster. Says David Meeker, a 30-year-old real-estate developer and three-time beer-miler in Raleigh, North Carolina, “When the Australian Josh Harris ran the beer mile two years ago [setting the world record of 5:02 that Nielsen smashed], someone from our running group sent the link around. We said, ‘We have to do that.’” After Nielsen’s record run in April, Paul Woidke, a Web developer in Columbus, Ohio, spotted the video trending on Reddit. “We thought it would be fun to do our own,” says Woidke. So 10 runners from his track group gathered at an out-of-session junior high to run the beer mile, a first for them all. Woidke’s 9:30 performance netted him fourth place. They’re planning their second event for September.

More than anything, however, the beer mile owes its ongoing existence to the campuses of higher education. “I heard about it in college, as a joke or something a frat guy would do,” says Katie Williams, a business developer for a startup who runs with a Bay Area–based group which, she says, takes the event “very seriously.” She ran her first beer mile in March. “The fourth lap I felt absolutely horrible, dead legs, stomach sick. I came in second to last. But five minutes after you finish, you feel awesome.”

It may sound like a gas, but “it’s not all roses,” says Butler of beermile.com. Just finding a venue for a beer mile is close to impossible with open-container laws and rules forbidding drinking on school grounds, not to mention the repercussions if you’re underage or part of an athletic team; Butler knows of university runners who’ve been suspended from meets for their shenanigans. And when beer miles go viral, there are always a few critics who say publicizing such an event is inappropriate. The finger-wagging, however, typically stems from anonymous sources rather than notable figures in the running or medical communities. Comments on sites like YouTube, Reddit, and LetsRun are overwhelmingly positive. Butler, who is now 37, doesn’t completely disagree with critics. “I won’t defend a stupid decision a kid makes if they’re breaking the law or team conduct, so I’d be on the side of the naysayers—maybe that’s my old age at work,” he says. Without question, would-be milers should heed the “Have fun, be safe, and don’t do this if you’re not 21” advice of perhaps the most famous college kid turned beer-miler, Nick Symmonds.

Before Symmonds became an Olympian, he was a DIII student at Willamette University in Oregon specializing in the 800 and 1500 meters. In the fall of his junior and senior years, Symmonds and his teammates celebrated the end of the season with a nighttime beer mile (they lit the track with their cars’ headlights). “It was kind of a time-honored tradition at the end of a cross-country or track season—a cool way to let off steam,” says Symmonds. “I could run it pretty well—5:30 or 5:40.” (In 2005, he was 11th on the beermile.com leaderboard, with a 5:31.)

By 2012, Symmonds was an Olympian in the 800, could run a mile in 3:56, and wondered what he could do in the beer mile. He decided to take a whack at the current record of 5:02 and post the attempt on YouTube. “I’m trying to grow the popularity of track and field by relating it to someone who doesn’t care what I run in the 800 meters,” he says. “We need to do more to draw the average fan in.” He ran a 5:19 (an American record that stood until Nielsen crushed it in April), and felt horrible. “The worst part is when you start running, you’re burping and trying to breathe at the same time. It’s like being waterboarded,” says Symmonds. “Then it’s dealing with the cramp and trying not to throw up. It’s a unique pain.” (Symmonds, by the way, did not flip the beer over his head for any of his laps, either.) The YouTube video of Symmonds’s record run was posted by TMZ, discussed on ESPN—and reached 100,000 views.

Beermile.com’s Patrick Butler remembers thinking at the time, It’s never going to get any bigger than that.

But then came James Nielsen. Inspired by the 60th anniversary of Roger Bannister’s sub-four-minute mile, Nielsen, an accomplished (but unofficial) 5:17 beer-miler in college, set his sights on shattering a similarly impossible milestone: four beers and four laps in under five minutes. He spent a year training his legs and his gut to break a barrier almost as mythical, in some circles, as the four-minute mile. Before Nielsen came along, preparation for the beer mile was what happened during track season or during what one might call “eating a big meal with a beer.” Post-Nielsen, it seems records are no longer the miraculous by-product of fast-twitch muscle fibers combined with innate chugging ability, but the result of careful study and stuffing yourself sick on occasion, all in the name of “training.” Sometime between Burlington Central High School and an April 28, 2014, YouTube video, the beer mile got…kinda legit.

So maybe it’s no surprise that in the wake of Nielsen’s sub-five, the track-and-field website Flotrack will host the first-ever Beer Mile World Championships on December 3 in Austin, Texas. Nielsen and John Markell, a former Queen’s University beer-miler, are also organizing a world championship in San Francisco, but the pair had to push off their original target date of September of this year; the event likely won’t happen until spring 2015. Says Markell, “planning has been a significant undertaking.”

The rise of the beer mile from novel invention to viral sensation has its creators scratching their heads. They say they never dreamed it would go from a lark with bragging rights and the opportunity to crack the top-10 T-shirt list to a competition that—if performed too well—can incite the masses. What do they think of all the discontent around Nielsen’s beer-mile behavior? Hell, they can’t even remember when they started turning cans upside down over their heads to signal an empty, or why or when, exactly, such a move was included as merely an asterisk in the rules. And they certainly don’t think Nielsen doctored his Budweiser. How did members of the original crew react to Nielsen’s record? Like the rest of us. With wonder.

Its popularity, however, may just be a sign of the times. As one of the early adopters of the beer mile, Markell believes the event has simply reached a critical mass. “Even the average Joe runner wants to see if he can finish it. The beer mile seems to have transcended the ‘This looks really unhealthy’ view, and become a physical challenge, which are in vogue these days.” Indeed, there seems to be no shortage of the willing when it comes to pushing limits: Participation in marathons has jumped 40 percent in the past 10 years, according to Running USA, and entrants in obstacle races have skyrocketed from 50,000 in 2010 to 4 million in 2013. “People love competition,” says Mark Floreani, cofounder of Flotrack. “The beer mile is part dare, part competition, and entertaining to watch.”

It’s part bonding experience, too. “Distance running has always been a sport of camaraderie that often extends to social lives,” says Markell. “Beer-miling is a weird but natural extension to the social aspect—why not suffer together doing something fun? I think it will continue to rise in popularity. It’s fun and hard and has finally surfaced beyond the cultish group of running circles.”

And despite the considerable lack of sanctioned venues in which to drink and run, and the considerable discomfort involved in doing so, there’s no denying the attraction between runners and beer. “There’s something embedded in running culture, the tendency to cut loose with beers after a run, and to want to put them together,” says Ian Fallas. “The beer mile is probably something that was just bound to happen.”

Story Update · April 28, 2016 Since we ran this story, Beermile.com has grown to include more than 93,000 entries from 2,950 beer-mile races—and James Nielsen’s record of 4:57 has been topped four times. The current champ (as we write this) is Lewis Kent; the Canadian ran a 4:47 at the second annual FloTrack Beer Mile World Championship in Austin, Texas, in December, an event that attracted 300 runners and 2,500 spectators. His record run came two weeks after Kent announced a two-year sponsorship with Brooks—the first such deal with a beer-miler—and a day after he appeared on the Ellen DeGeneres Show and challenged one of her staff members in a beer race. At that same Austin event, Erin O’Mara set the current women’s record of 6:08. (Both winners took home $5,000: $2,500 for their wins, and $2,500 for the records.) The event’s former king doesn’t see the race’s popularity dwindling anytime soon. “People have always been fascinated by footraces, and when you combine that with partying, it’s even more exciting,” says Nielsen, who helped launch the Beer Mile World Classic in San Francisco last August. “I think we’re just seeing the beginning with the beer mile.” Writer Rachel Swaby, who has never chugged and sprinted herself, agrees: “I don’t think it has peaked. It’s just become more mainstream, which means there will likely be more competitions to come.” And she’s right. Nielsen is bringing the Classic to London on July 31. —Nick Weldon