Carl Schmitt serves as a negative exemplar, illuminating the dangers against which classical liberalism must guard.

Niebuhr's Christian Realism

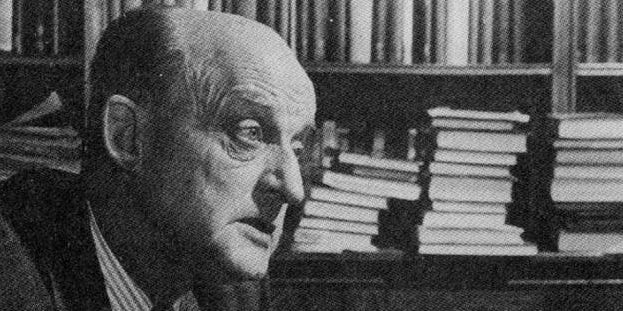

Possibly excepting Martin Luther King, Reinhold Niebuhr likely was the most important American political theologian of the 20th century. Few have repeated his success in deep thought that has often been translated into pithy proverbs. And few have equally understood America’s intrinsically Protestant character.

Gregory Moore’s Niebuhrian International Relations offers the latest interpretation of the Christian Realist’s perspective. Although commonly associated with moral analysis of war and peace, Niebuhr never wrote a specific book about global statecraft. So Moore offers a brief biography and tries to apply Niebuhr’s thought to contemporary challenges such as the Iraq War, humanitarian military interventions, and China’s ascendancy. Although emphatically a Protestant, Niebuhr’s insightful application of “Christian understandings of truth to real-world problems in various fields” invited non-Christians into his realist worldview. David Brooks has observed that Niebuhr was “every atheist’s favorite theologian and every conservative anti-communist’s favorite liberal.”

Moore’s overview of Niebuhr is timely, helpful and approachable for a broad audience. Maybe it is most useful for today’s American Christians who feel politically displaced but refuse to despair. For them, Niebuhr’s Christian Realism might be a tonic.

Niebuhr was both realist and liberal, shaped by Kierkegaard, Dostoyevsky, Nietzsche, Heidegger and Tillich, all of whom affirmed the importance of personhood, though Nietzsche’s version set itself against Christianity. Other realists hailed Niebuhr, with George Kennan calling him “the father of us all.” Hans Morgenthau cited him as “the greatest living political philosopher of America.” Paul Ramsey called him a “theistic existentialist.” Moore affirms Niebuhr believed in objective truth but was relativist about the capacities of human knowledge and wisdom, warning against claims of possessing absolute truth, theological or rationalist. Human limitations required openness to other approximations of truth. In this sense, Niebuhr’s message of humility is especially needed for a society even more pluralistic and diverse than in his day. Today’s polarization and tribal loyalties need his reminder that sinful, finite humans should never be too certain about themselves. Grace, mercy, listening and tolerance must be extended to others, Niebuhr would remind us.

The son of German immigrants, Niebuhr became a lifelong acolyte of American democracy. He followed his father into the pastorate of a German Reformed denomination and studied at Yale Divinity School, later teaching for several decades at Union Seminary in New York. As a young man he was a socialist and Social Gospel enthusiast. World War I helped turn him pacifist, and WWII in due course convinced him of the need for just military force. Like many American Protestants, he backed America’s entrance into WWI as a moral imperative, only to be disillusioned by the war’s failure to establish a just peace that lived up to idealistic expectations. Axis aggression awakened him from such idealism and inspired his appreciation for tragedy and paradox. He seemingly remained a theological liberal, too much so for today’s Catholics and Evangelicals, Moore thinks. Niebuhr rejected biblical literalism. And he found Billy Graham’s “wholly individualistic conceptions of sin” to be “almost irrelevant” to contemporary social problems.

But Niebuhr in the 1930s became firmly Augustinian about human nature, which informed his Christian Realism. In short, he was pessimistic about humanity but hopeful about God. Niebuhr’s outlook on international relations was always measured, as evidenced by his view that: “Perhaps the best that can be expected of nations is that they should justify their hypocrisies by a slight measure of real international achievement, and learn how to do justice to wider interests than their own, while they pursue their own.”

Lifelong Democrat

As Moore recounts, Niebuhr was a New Dealer and lifelong Democrat who aimed much of his concern at progressives with soaring ambitions for transforming society. He warned that “secular and religious idealists hoped to change the social situation by beguiling the egoism of individuals, either by adequate education or by pious benevolence.” Such idealists were prone to ignore the temptations and corruptions of power in statecraft, he warned, as “no group acts from purely unselfish motives or even mutual intent and politics is therefore bound to be a contest of power.”

In global statecraft, Niebuhr regretted that idealists “do not recognize to what degree justice in a sinful world is actually maintained by a tension of competitive forces, which is always in danger of degenerating into overt conflict, but without which there would only be the despotic peace of the subordination of the will of the weak to the strong.” Niebuhr suggested “a realist conception of human nature should be made the servant of an ethic of progressive justice.” But the path to such justice was always strewn with unintended consequences amid complex human intentions. Yet approximate justice must be sought.

Although Niebuhr did not write a comprehensive book specifically about international relations, as Moore explains, he did establish Christianity & Crisis magazine in early 1941 to persuade Protestant pacifists and isolationists, who had been ascendant during the 1920s and 1930s, to support the Allies against Axis aggression. During the early Cold War years Niebuhr continued his editorial crusade for Western solidarity against Soviet totalitarianism, which he summarized with this argument:

We must be on our guard lest those who regard the peace of the Kingdom of God as a simple alternative to the difficult justice and precarious peace of the world deliver us into a peace of slavery. They would not do it willingly; but they willingly nourish illusions that obscure the difficulties of achieving justice and the sorry realities of a peace without justice.

Moore notes Niebuhr was an anti-Communist liberal, who helped found Americans for Democratic Action, who supported labor unions and social reforms, including civil rights, and who warned against religious bigotry. Niebuhr was an early supporter of Israel and cited the Hebrew prophets in his own call to national humility with morality. But he warned morality between nations was far more complex than among individuals. The Ten Commandments and Sermon on the Mount were not directly applicable to international relations. Turning the other cheek, as Jesus commanded in personal relations, would in statecraft require responding to Pearl Harbor by inviting the Japanese to bomb San Francisco.

Affirming particularity, for the Jews, for America, and for the North Atlantic democratic community, Niebuhr still warned against tribalism as the “chief source of man’s inhumanity to man.” His public life concluded with opposition to the Vietnam War, and President Nixon.

Pragmatist or Just Warrior?

Moore rightly notes that Niebuhr is often cited as a proponent of the Just War tradition even though some Just War theorists complain that Niebuhr’s arguments for force were more pragmatic than rooted in traditional church teaching. Characteristically, Niebuhr noted: “In statecraft, consequentialist considerations must be part of the calculus, for policymakers cannot afford purely abstract deontological reasoning, but rather must root their policy choices in realities of a morally broken world in which we all live.”

Harsher critics sometimes allege Niebuhr was a default consequentialist with a dark view of human nature but no specific corresponding redemptive Christology. Moore responds to these critics partly by arguing Niebuhr aligned with but typically did not cite specifically Just War teaching. More broadly Niebuhr argued for a “love ethic” sometimes requiring violence in defense of justice and the innocent. But he always warned against moral preening in such choices, however imperative, as “these commitments (in the cause of justice) may involve us at times in war and that at all times they involve us in moral ambiguity.”

Niebuhr was a dialectician and liked to cite paradox and the inevitability of tragedy even amid hope. Moralism, piety, and sentimentality, however lofty, could be unintentionally destructive and even calamitous in politics. Society sometimes need protection from the do-gooders. As Union Seminary President John Bennett explained of his longtime colleague and friend:

Niebuhr rejects the idea that love can take the place of justice, if those who love only become more loving. No, there must be structures of justice to enable people to defend themselves against the loving who are so sure that they know best what is good for others.

Moore is persuasive that Niebuhr, who died in 1971, would have opposed the Iraq War, just as he opposed the Vietnam War.

Moral Dualism

Moore suggests moral dualism may be Niebuhr’s most important insight on political morality. Niebuhr criticized and affirmed the 1945 atomic bombings, and the Korean War. He championed American global responsibility while constantly warning against overreach. Shunning unalloyed idealism, Niebuhr insisted the pursuit of self-interest was inevitable for both persons and nations. Such pursuits could be collaborative and enlightened but also could be sinister and irrational.

As, at least from the Augustinian perspective, human nature never changes, so too did Niebuhr believe that the world’s competitive and often violent nature never changes. War and conflict are fruits of human pride and constant possibilities. But divine grace among fallen humanity, and the human desire to survive, argue against yielding to the worst outcomes. Humanity always has the providential means to do better, even amid peril.

“For peace we must risk war,” Niebuhr noted with typical brevity, as he defended nuclear deterrence, weighing the horror of atomic destruction versus Soviet global domination. There are never ideal solutions in statecraft for Niebuhr, who disdained perfectionism and who sought to avoid superficial piety, like the pre-WWII Christian pacifists he debated. “There is no possibility of making history completely safe against either occasional conflicts of vital interests (war) or against the misuse of the power which is intended to prevent such conflicts of interests (tyranny),” Niebuhr surmised.

Moore says Niebuhr’s Christian Realism is “more nuanced than the rather raw, brute materialism implied in most other Realisms” and is more attentive to “human idiosyncrasies.” Also, Niebuhr’s version contrasted with other realisms in international relations by affirming that national interests could be fixed and are conflictual but must allow for human agency and local particularities. It’s also important to include Niebuhr’s appreciation for redemptive providential agency. In his view, God sustains what humanity might otherwise destroy.

Chiefly Niebuhr was concerned to sustain the centrality of human personhood. As Moore notes: “Niebuhr believed that humans are material creatures imbued by their creator with divine qualities and behavioral potentialities due to the imago dei, their having been created in the image of their creator, as argued and believed in traditional Christendom.”

Through Niebuhr’s Christian Realist prism, Moore specifically examines Niebuhr’s thought through chapters on human nature, collective society, globalization, the Cold War, the Just War tradition, humanitarian interventions, China’s ascendancy, and contemporary international relations theory.

Careful Cold Warrior

Although a Cold Warrior, Niebuhr saw the struggle, as Moore describes, as not “mainly a bipolar struggle in material driven security spiral but one of two belief systems and two regime types.” Perhaps mindful of his own family’s roots in German authoritarian culture, Niebuhr “adored” democracy but always warned against Western hubris. He initially disapproved of Churchill’s Iron Curtain speech, though he later imitated the speech in his own sharp rhetoric. Niebuhr contrasted Nazism’s limited appeal to universalist Communism, which he called “the most dynamic and demonic world politico-religious movement in history.”

But Niebuhr’s chief jeremiad of his career was against appeasing the Axis. Japan’s invasion of Manchuria posed a special impending threat to world order, he saw, and foreshadowed many more aggressions. Nazism, in its exaltation of strength over weakness, was the world’s first great revolution against Christianity. The German occupation of Vienna represented the “final destruction of every concept of universal values upon which Western civilization has been built.” America’s Neutrality Act, forbidding special aid to the Allies, was “one of the most immoral laws that was ever spread upon a federal statue book” and showed the “essence of immorality is the evasion or denial of moral responsibility.”

Moore is persuasive that Niebuhr, who died in 1971, would have opposed the Iraq War, just as he opposed the Vietnam War, viewing the Viet Cong more as nationalists than communists and being skeptical of Asian land wars. But Moore may underestimate Niebuhr’s hypothetical concern about Saddam Hussein as tyrant and aggressor. Both supporters and opponents of the 2003 war cited Niebuhr. Moore admits that Niebuhr’s realism would preclude an absolutist demand for United Nations approval of all military actions. And he says Niebuhr would be more hawkish and internationalist today than most contemporary realists. As a Christian Realist, Niebuhr strongly affirmed America’s moral responsibility to defend not just its own interests but also democracy and moral order in the world.

Niebuhr would disapprove Donald Trump based on narcissism and hubris, Moore says. He would readily understand the need to counterbalance Russia under Putin. And he would be a China hawk, seeing the dangers of its insecure dictatorship, its master narrative about Chinese authoritarian superiority, and the natural human desire to exploit wealth and power. Niebuhr doubted China’s capacity for democracy, noting that Confucian culture succumbed to communism because of the “lack of individual independence and the strong emphasis upon prudential rather than heroic virtue.”

Freedom Not Absolute

More widely of non-Western cultures, Niebuhr thought “their religions either lose the individual in the social whole, the family, or the tribe (as in Confucianism and in the more primitive religions of Africa), or are mystical religions which seek for the annulment of individuality.” He surmised that even if they could appreciate individualism, they must still reconcile liberty with stability, since “freedom is not an absolute value.”

Niebuhr believed democracy requires “some capacity of the individual both to defy social authority on occasion when its standards violate his conscience and to relate himself to larger and larger communities than the primary family group.”

Moore’s history and interpretation of Niebuhr’s wary Christian Realist perspective on global statecraft is a needed corrective to today’s dogmatisms and certainties. Niebuhr in his day contended against political and religious idealism. His perspective is needed now against pessimism, despair and apocalyptic attitudes. For Niebuhr, the only sure certainties are human frailty and God. As Moore competently and succinctly explains, a Niebuhrian never hopes too much in humanity nor trusts too little in a kind and merciful Providence.